From Doctor to Patient

Laura Liberman’84 felt it first in her fingers. As a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center radiologist with expertise in breast imaging, she often conducted needle biopsies on her patients, a procedure that required a steady hand. But in early 2007, she found that she had to work harder to achieve her usual dexterity. An appointment with a neurologist led to two months of diagnostic hoops. At the end of it, Dr. Liberman learned she had stage 4 lymphoma that had spread to her lymph nodes, bone marrow, spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid.

Her doctors told her she had a 50 percent chance of remission and started her on a six-month course of intensive treatment. “It was a very odd experience to be a cancer patient where I had been a cancer doctor for so many years, being on the other side of those conversations,” she recalls. “It was like being in a play where you know all the lines, but they have you reading the wrong part.”

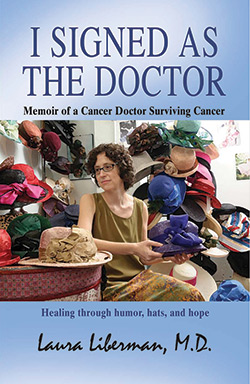

Dr. Liberman came out on the good side of the odds. A lifelong writer, about six months after finishing treatment she set out to pull all of the writing she had done during that time—much of it in the form of emails to a close friend—into a book, “I Signed as the Doctor: Memoir of a Cancer Doctor Surviving Cancer.” Her motivation was equal parts of wanting to inspire and soothe patients and seeing the value of offering a doctor’s take on elements of a patient’s experience that clinicians might overlook.

The science driving cancer care has changed tremendously in the past decade. Dr. Liberman, for one, received conventional chemotherapy, but she also was treated with a monoclonal antibody called rituximab, which targets malignant lymphocytes and leaves most healthy cells alone. Many newer treatments are easier for patients to tolerate and can be done on an outpatient basis. Advances in relieving symptoms of nausea also have improved cancer care. Still, she says, “as a doctor I realized that many symptoms can be managed, so I knew I could ask.” Sometimes patients do not know what to ask.

She also realized that cancer doctors tend to be so focused on curing the disease that pain relief may take a back seat. Yet for patients, even minor pain adds up and becomes just one more thing to dread during a course of treatment. “I really appreciated that when I was on the other side,” she says. She took to carrying around topical anesthetics that she could apply before procedures, and since migrating back into her role as doctor, she has worked to make colleagues and trainees more aware of the need to alleviate pain.

These days, Dr. Liberman does not deliver direct patient care. After returning to work in 2008, she transitioned to a more administrative position in the office of faculty development, where she leads programs for women and junior faculty. She also organizes a yearly course addressing the recent explosion of scientific advances in cancer research. The courses are attended by almost 300 people—doctors, students, fellows, faculty members at all ranks, nurses, medical editors and illustrators, and even folks from the grants office. “It’s been a wonderful opportunity to bring people together,” Dr. Liberman says. And, also, to keep the words flowing: Each topic covered in the lectures starts off with a poem she writes for the occasion.

- Log in to post comments