Alumni Profile: Henry Shinefield’48

Henry Shinefield, 96, at home in New York City, holds a photograph of himself as a child. Photo Julia Hickey.

Henry Shinefield, 96, at home in New York City, holds a photograph of himself as a child. Photo Julia Hickey.Henry Shinefield’s first “Eureka!” moment took place in the newborn nursery at what is now NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell. The discovery, to be exact, was in the nasal mucosa of newborn babies.

It was 1960, and a virulent strain of staphylococcus aureus (“staph”) bacteria called 80/81 was spreading through hospital nurseries worldwide, invisibly clinging to babies who acted as sleeper cells for their households. Weeks or months after leaving the hospital, the babies developed serious symptoms of staphylococcal disease, which in turn sickened their caregivers: mothers with breast cellulitis, fathers with septicemia, siblings with meningitis, grandparents with pneumonia. The bug was resistant to penicillin, the main antibiotic used at the time. Once 80/81 settled into someone’s nose or belly button—its preferred digs—it was nearly impossible to evict.

Dr. Shinefield, a young pediatrician, had been invited to Weill Cornell to get to the bottom of this epidemic. He had already served during the Korean War in the inaugural cohort of the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) of the U.S. Public Health Service, a band of disease detectives who work to investigate and prevent outbreaks. He later spent five years making house calls as “le doctore” to the largely Italian population in north New Jersey and would go on to orchestrate large-scale trials to approve vaccines for children across the globe. He knew that our skin, orifices, and entrails were always crawling with bacteria and that many bugs were harmless. Even some bad bugs were content to cohabitate with us, never activating their fullest wrath.

“There were many bugs that we got involved with and we made some bets with,” says 96-year-old Dr. Shinefield as if narrating film noir, “and let me tell you, 80/81 was a bad bug.” The bacteria, abscesses, and corresponding blame would bounce around the family for months or even years. “The kind of horror that went on you can’t believe. People sold houses in order to get rid of the bug,” he said. But little did he know, 60 years ago, that staph bacteria in its various strains would become a lifelong fascination and foe.

For the babies of Weill Cornell, it became clear that a nurse with 80/81 lodged in her nose was the initial colonizer. She was removed from the nursery, but Dr. Shinefield was on to something: When infants were handled by the infected nurse within the first 24 hours of life, some contracted 80/81 (22%). But when she cared for babies on their second day of life, none became infected. They did, however, test positive for other strains of staph, which were apparently harmless.

Dr. Shinefield developed a term as well as a hypothesis—“bacterial interference”—to suggest that staph bacteria might compete for terrain. Once one settles in, it may prevent others from colonizing or thriving. He found a particular staph in the noses of all the healthy babies: strain 502A, belonging to another nurse. The babies she held within 24 hours of birth did not get sick, and they did not infect their families. So he studied 502A, ruling out associated diseases and ensuring it could be killed with penicillin.

What came next would not be so easy in today’s medical landscape: After speaking with the babies’ parents, Dr. Shinefield and his colleagues tested the hypothesis by inoculating 502A into the babies’ noses. And it worked. Babies with 502A were drastically less likely to be colonized by 80/81 than babies in a control group.

“It was a little audacious,” says Paul Planet, MD, PhD, who revisited Dr. Shinefield’s pioneering work in bacterial interference in a 2019 paper co-authored by Dr. Shinefield. In the 1960s, medicine was focused on destroying pathogens in the clinical setting, not harnessing their powers. Dr. Shinefield soon took 502A on the road, and 80/81 began to disappear from nursery wards across the country and the world.

“I’ve been very lucky. In research, you can be very good at what you are doing and it won’t work, and it’s not your fault. Or if you are lucky, things will turn out,” he says.

By 1971, 4,000 newborns across the country had been successfully inoculated with 502A. But as the epidemic caused by 80/81 waned, so did the interest in bacterial interference—at least for the next several decades.

The School of Life

“My father got off the boat and the first thing he did was kiss the ground and say, ‘America, I love you,’” is a story Dr. Shinefield re-tells as vividly as if he were there on Ellis Island in 1906 to see it. His parents were Jews who fled Ukraine in their early 20s. They settled in Paterson, New Jersey, then known as America’s “Silk City,” and opened a small mill.

Henry Shinefield, pictured here in his uniform in 1951, was one of the first 20 members of the Epidemic Intelligence Service of the U.S. Public Health Service.

Henry Shinefield, pictured here in his uniform in 1951, was one of the first 20 members of the Epidemic Intelligence Service of the U.S. Public Health Service.Born in 1923, Henry was the fourth child and baby of the family by more than a decade. He was initially thought to be a tumor in the belly of his 40-year-old mother, until the tumor was found to have a heartbeat. His sister, Terri, who was 17 years older, taught him to sing and tap dance and paired him up with a girl named Jane Pritchard to perform at variety shows, conferences, and parties by the age of 6. (Seventy years later he and a colleague were stopped on a New Orleans sidewalk by a boy tap dancing for change. Dr. Shinefield handed over a dime before swaying into his own soft-shoe routine. “You should have seen the look on the boy’s face,” he said.)

Young Henry also helped his father in the mill, running his hands across silk skeins to pick off the imperfections until 1938 and the fallout from the Great Depression brought the 20 looms to a halt.

“I was in the house when the telephone company man came in and he took our phone out of our house because we couldn’t pay a $2.50 bill,” he said. Despite the hardships, the Shinefields remained positive. The eldest brother, Maurice, was completing medical school to become one of the first board-certified pediatricians in the country and soon opened a practice in the front half of their home. His mother sewed clothing with the WPA and his father became a middle-man in textiles and paid back every loan for his defunct silk mill, despite their having been discharged in bankruptcy.

“I think a positive attitude is part of success in general,” Dr. Shinefield says. “My father told me, ‘You can do whatever you want, but the one thing you must not do is you can’t hurt anybody.’ I have never forgotten that.”

Another favorite story from his childhood: “People would tell my brother, Maurice, ‘Your family is quite poor.’ He would get indignant. He would say, ‘Sometimes we were short on cash, but we were never poor. We were wealthy with love.’”

At the age of 16, he was invited to a party with a “well-to-do young lady” but was contemplating canceling because he didn’t have a proper jacket. His brother, Michael, gave him all his money, a total of $17. “I ran out and bought the most wonderful green jacket you could possibly imagine and went to the party with pride,” Dr. Shinefield said.

He attended Columbia College and later VP&S, graduating in 1948 with plans to join his brother in pediatric practice, but not before his residencies and military service taught him to think like an epidemiologist.

As the only unmarried resident in his division at Duke University in 1949, he was sent in the heat of July to a polio outbreak in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where, stripped down to his undershirt, he and a nurse carried out the Sister Kenny method of using moist, hot blankets on children’s legs to ease their spasms. Polio is an inflammation of the spinal cord that can cause disability, paralysis, or death, and any sign of a limp or cough could send mothers into terror. When a boy was set to receive a midnight tracheostomy for suspected respiratory failure but instead coughed up an intestinal worm, “it was all smiles” for once, he reminisces.

“You are not a hero each time,” he says of the losses. His message for anti-vaxxers: “You haven’t seen what I’ve seen. Because if you have seen what I’ve seen, you wouldn’t say you don’t believe in vaccines. Vaccination is the cardinal item we have for disease prevention.”

As one of the first 20 EIS officers in the nation, he was sent on a 10-hour prop flight to California. After noticing that a pregnant woman infected with Western equine encephalomyelitis (who later gave birth to infected twins) was known to sleep in a Bakersfield backyard, he chased down the neighboring chickens to test their blood. He found that they were asymptomatic carriers of the disease, which is transmitted through mosquitoes.

While investigating cases of hepatitis in the coal mining town of Harlan, Kentucky, he learned to cover the official insignia on his car to avoid the ire of moonshiners with squirrel guns. But when Dr. Shinefield eventually returned to New Jersey for 14-hour days of pediatric house calls with his brother, those tables would be turned: He couldn’t get out of Italian patients’ homes without ravioli, bread, cannolis, or, from Mafiosos, promises they would take care of any “problems” he had.

“Well, thank you very much. I am not sure I’ll need anything like that!” he said. “It was an exciting time.”

Thinking Big

In 1985, Dr. Shinefield was chief of pediatrics at Kaiser Permanente Medical Group in San Francisco, where he was on staff from 1965 to 2005. Started in California in the 1940s by ship-builder Henry Kaiser to care for his thousands of employees and their families, Kaiser Permanente is now a pre-paid, nonprofit health plan with more than 12 million members in several states.

Dr. Shinefield encountered the nascent medical group in 1950, when he visited a clinic that was “literally medical offices over a drug store” in San Francisco. Later, large hospitals were built that contracted with doctors to coordinate all aspects of patients’ care. “Whatever was needed and how it was needed—prescriptions, drugs, procedures—was all done by the physicians. What Kaiser Permanente had was a tree that was planted in earth, not sand, and it was going to grow,” Dr. Shinefield said, adding that he believes this is the best model for American medical care.

At a pediatrics meeting, Dr. Shinefield met a scientist named David Smith, who founded the laboratory Praxis Biologics and developed a vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae (Hib) that was tested and used in Finland. In the United States, the vaccine was only temporarily approved by the FDA on the condition that a large phase 4 clinical trial be conducted.

Dr. Shinefield’s second “Eureka!” was the realization that the full Kaiser Permanente tree, with its research talents, technology, and well-monitored patient population—like a full flowering of leaves—could be used for large-scale vaccine trials.

From June 30, 1985, to May 31, 1987, 120,000 children at Kaiser Permanente were immunized in a controlled study, and four became ill with Hib meningitis during the first week following immunization. This was 6.4 times greater than could be expected when compared with a matched control group (p=0.001) and revealed what the small Finnish study had missed: The vaccine was not safe.

“This wasn’t like a little pimple on the nose. This was something significant,” Dr. Shinefield says. It also revealed the importance—in fact, the necessity—of such a large sample set to approve vaccines. So Dr. Shinefield and his colleague, Dr. Steve Black, developed the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center, which was soon flooded with requests. They worked with Praxis to complete phase 3 and 4 trials for new and improved vaccines for Hib and pneumococcus and with several companies to study vaccines for acellular pertussis (DTaP); adult pertussis (Tdap); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); nasal influenza; rotavirus; papillomavirus (HPV); hepatitis; and varicella. They also collaborated with the CDC to create the Vaccine Safety Data Link, an electronic health data project to monitor adverse events following immunization.

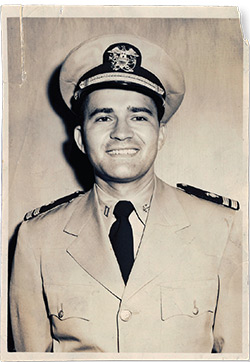

A 1990 photo shows Henry Shinefield and patients while serving as chief of pediatrics at Kaiser Permanente.

A 1990 photo shows Henry Shinefield and patients while serving as chief of pediatrics at Kaiser Permanente.Dr. Shinefield and Dr. Black traveled around the globe with their vaccine work. “A lot of the world was opened up to me because of medicine, because of what we did,” he said. “What I learned in medicine: Humanity is more alike than diverse. The aims and ideas and hopes are similar, and people are more similar than dissimilar. It’s amazing.”

Ultimately, the FDA gave full approval for Hib and pneumococcal vaccines that are used worldwide. These two vaccines have effectively eliminated the most prominent causes of infant and childhood bacterial meningitis. The pneumococcal vaccine is also recommended for use in adults.

“This for me was the epitome of career success,” Dr. Shinefield says.

But when talking about success, he always pivots to the personal, adding that the best thing to ever happen to him was meeting his wife, psychologist Jackie Shinefield. The two were introduced in 1981 and ran up a $3,000 bicoastal telephone bill in the course of their long-distance courtship. “The phone bill is getting crazy,” he joked with her. “We have to get married now.”

“Love, Henry”

“Nature abhors a vacuum, of any kind, and there is always something to fill it.”

Over Earl Grey tea in New York City, Dr. Shinefield is describing the invisible wilderness of bacteria and organisms that compete to live in and upon us.

Case in point: When a four-mile walk caused a small blood blister on his heel, a strain of staph settled in and bloomed into necrotizing fasciitis.

“He would have died within hours,” Jackie remembers the doctors telling her that day in 2001 when his painful symptoms emerged in full force. He had six surgeries to save his foot and his life.

“Staph got even with me,” he quips. But in addition to the irony that the man who once eliminated a strain of staph from hospital nurseries was almost killed by staph, he also focuses on the science. “What the factors were to make the bug invade the bloodstream under those circumstances, whether it was the heat of the foot or exactly what turned it on, well, we don’t know.”

Staph has evaded all attempts so far to submit to a vaccine, because it unpredictably cloaks and times its ability to become virulent. Just what causes staph strains to sometimes co-exist with, harm, or even protect their hosts through bacterial interference is a lifelong question that Dr. Shinefield is hoping a new generation of scientists will answer. Some of them are his three co-authors of a 2019 paper published in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal titled “Revisiting Bacterial Interference in the Age of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.”

Jackie and Henry Shinefield in 2006.

Jackie and Henry Shinefield in 2006.Paul Planet, a co-author, is working with new genetic techniques to examine how the nurse’s staph strain 502A in 1963 caused bacterial interference. “If it could have been done in 1963, he would have done it,” says Dr. Planet. “Now we’ve finally caught up to the place where we can test Dr. Shinefield’s thinking.”

Because antibiotic-resistant staph bacteria are on the rise, the days when it will fully evade treatment are on the horizon. Science also offers new understanding of the immune system and a renewed interest in the concept of a microbiome for protection, and Dr. Shinefield is hoping for the day that bacterial interference can be put to practical clinical use.

“To be alive to see that be reconsidered now, after the early stuff we did: That’s what’s really exciting for me.” In fact, everything seems to be exciting to Dr. Shinefield, who exudes gratitude. He is in the habit of signing all his correspondence—with everyone from his wife to Dr. Planet to the president of the National Academy of Medicine—with “Love, Henry.”

And he’s not hungry for credit. “I am happy. I am the fourth author. I have published 260 papers. I don’t need any more papers. And, let me tell you, they don’t have a committee up in heaven to evaluate all this, and so I am not concerned about that,” he said

- Log in to post comments