"Medical Fellows" and the New York Game

Columbia has more than a passing association with the game of baseball. History buffs know that the Highlanders (before they were the Yankees) played on land that is now occupied by the medical center garden, where a symbolic home plate installed in 1993 is expected to be returned when garden construction is completed. And P&S has long had ties with Cooperstown, N.Y., where many a medical student has visited the National Baseball Hall of Fame while rotating through Bassett Medical Center.

Although confusion remains about the game’s origins, the sport of baseball as we know it began as a city game. Called the “New York Game,” it began to attract newspaper coverage in the 1840s and early 1850s, when it was played by members of the Knickerbockers and a few other Manhattan-based clubs. A surprising number of these early baseball players were physicians, many of them graduates of the College of Physicians and Surgeons during the period of time when Columbia medical school faculty had merged with faculty in the independent P&S. The early baseball players were amateur, part-time athletes with full lives off the field. Most of them played for fun. A few visionaries, however, such as Brooklyn’s Dr. Joseph B. Jones (P&S 1855), saw in this obscure regional pastime an instrument to improve the lives and health of a nation.

Knowledge of baseball before the Knickerbockers is fragmentary, but the game seems to have had a long association with Columbia College and P&S. New York City physicians, particularly alumni of P&S, played the game from its earliest days. In 1887, the San Francisco Examiner published an interview with William Wheaton, a 73-year-old New Yorker who had gone to California in the 1849 Gold Rush. Mr. Wheaton recalled that in the 1830s he had played in a pickup baseball game on the Lower East Side of Manhattan made up of “merchants, lawyers, and physicians.” This game was formalized as the “New York Base Ball Club” in 1837; one of its founders was 1829 P&S graduate John Miller, a popular doctor who lived and practiced at 186 E. Broadway. (This is the same “New York Club” that defeated the Knickerbockers in Hoboken, N.J., on June 19, 1846, in what is often misidentified as the first baseball game). An 1896 interview with Daniel “Doc” Adams, who moved to New York after graduating from Harvard Medical School, corroborates Mr. Wheaton’s story. Dr. Adams recalled playing with the New York club in 1839, before he and “several of us medical fellows” switched to the Knickerbockers, who were organized in 1845. He did not name names, but Knickerbockers records contain a number of prominent physicians, including William B. Eager (P&S 1848), who was chief of staff of City Hospital on Blackwell’s Island and professor of gynecology at Bellevue, and Francis Upton Johnston Sr. (P&S 1820, P&S Trustee 1827-1837).

Why were physicians drawn to baseball? The answer to this question tells us quite a bit about why and how a simple game, played mostly by children, evolved into America’s first national team sport. Today, in a society in which professional sports occupy so much cultural space, it is hard to imagine life without them. Before the Civil War, however, America had no leagues, championships, stadiums, sports fans, or even a word for fan. The few organized sports that were popular, such as horse racing and boxing, catered primarily to bettors, not participants or spectators. Not only did Americans of the mid-19th century have no national team sport, most saw no need for one. One reason was the belief, inherited from the Puritans, that play was for children, not adults. An emerging reform movement set out to change this. Conspicuous among the reformers were Protestant clergy who preached “muscular Christianity”—the ideology behind the YMCA—and physicians. Physicians, of course, saw firsthand the health consequences of their middle class patients spending their days sitting at a desk and their nights eating, drinking, and smoking. Medical experts of the time also attributed common diseases such as tuberculosis to sedentary lifestyles. Influenced by the English reformer Sir Edwin Chadwick, the father of modern public health, progressive American physicians advocated for exercise for adults and physical education in schools. It was a long, uphill fight, and baseball was not their first choice of weapons. As early as the 1820s, boxing gyms opened in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Despite being endorsed by local medical establishments, they ultimately failed to market boxing to middle class gentlemen as a respectable participant sport, the “manly art of self-defense.”

Physicians and their entrepreneurial allies made another attempt to sell exercise to the American public by importing gymnastics and weight training from Great Britain and Continental Europe. In 1833 English boxer William Fuller opened one of New York City’s first gymnasiums at 29 Ann Street, near City Hall. In an April 17 advertisement in the New York Evening Post, he states:

We esteem exercise, as an essential means to the preservation of health, and as one of the most certain prophylactics against those innumerable diseases, which result from a want of it. We, therefore, cordially recommend all sedentary persons, whose professional avocations debar them from the pursuit of health by the more common forms of exercise, to resort to this Gymnasium, where every species of muscular invigoration can be readily obtained, from the gentlest to the most athletic exercise.

It is a testament to the popular resistance to the idea of physical training for adults that Mr. Fuller felt it necessary to add a testimonial—(“We fully concur in the value of Gymnastic exercises”)—signed by the legendary Dr. Valentine Mott (P&S 1806) and nine other trustees, professors, and alumni of P&S, along with Columbia President William Alexander Duer and several faculty members.

Meanwhile, across the East River, in 1849 a ship captain’s son named Joseph B. Jones opened Brooklyn’s first state-of-the-art gymnasium at the corner of Pineapple and Fulton streets in what is now Brooklyn Heights. Tall and thin, Mr. Jones was a good amateur boxer and an excellent gymnast. Like boxing, however, gymnastics failed to achieve wide popularity as a participant sport. After vigorously promoting the sport for two years—including bringing in controversial English feminist Madame Beaujeu Hawley to teach gymnastics to women and girls—Mr. Jones sold his gymnasium and entered P&S to study medicine. There, Mr. Jones switched his focus to baseball. After graduating in 1855, he played for a Brooklyn club called the Esculapians. As its name suggests, it was made up of young physicians and medical students, most of them from P&S. (P&S grads continued to play with the Esculapians into the 1870s.) Shortly afterward, Dr. Jones joined the more competitive Excelsiors, Brooklyn’s first baseball club. Founded in 1854, the Excelsiors began as a kind of satellite of the New York Knickerbockers. Many of the early Excelsiors were well-off men with family, professional, or social connections to the older New York club. One of them was Daniel Albert Dodge, an 1852 graduate of P&S and visiting surgeon at Long Island College Hospital; another was Van Brunt Wyckoff (Columbia College 1840, P&S 1845), who made a fortune in Brooklyn real estate and used it to back the Excelsiors. Dr. Dodge’s cousin, Samuel Kissam, lived in Brooklyn; although Mr. Kissam was a prominent member of the New York Knickerbockers, his name appears in two box scores playing for the Excelsiors. He was a stockbroker, but he came from a family with a unique connection to P&S: 28 Kissams studied medicine there (including the Samuel Kissam who was one of the first two graduates of Columbia’s medical school). The socially exclusive Knickerbockers rarely played against other clubs, but in 1858 and 1859 they played a home-and-away series with the Excelsiors.

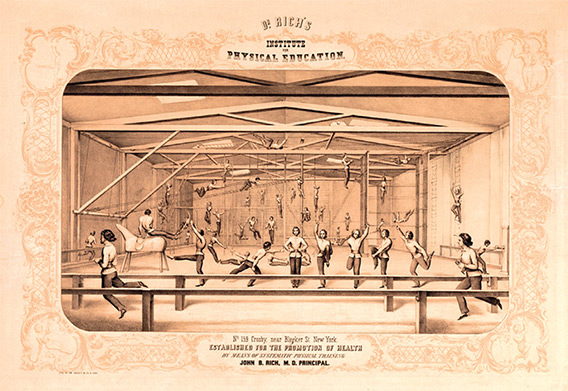

Physicians were among the health enthusiasts who opened gyms around New York City to promote physical fitness. Dr. John B. Rich opened this gym on Crosby Street in 1845.

Physicians were among the health enthusiasts who opened gyms around New York City to promote physical fitness. Dr. John B. Rich opened this gym on Crosby Street in 1845.For an ambitious young doctor looking for a way to sell Americans on exercise, Dr. Jones was in the right place at the right time. New York City, baseball’s birthplace, was the biggest and richest city in the United States. Then an independent city, Brooklyn was catching up fast, doubling its population each decade and beginning to see itself as New York’s competitor in trade, manufacturing, and culture. When both cities caught baseball fever in the 1850s, the sport became another arena in which the intercity rivalry played out. New clubs sprang up, eager to prove themselves against other clubs. To everyone’s surprise, spectators began to appear at these interclub matches, with those between Brooklyn and New York City clubs attracting the largest crowds. In July of 1858, for example, journalists were impressed that 3,000 people came to Carroll Park in Brooklyn to watch the Excelsiors defeat the New York Knickerbockers, 31 to 13. Later that summer, an all-star series that pitted Brooklyn against New York City drew excited crowds of more than 10,000. Sportswriter Henry Chadwick (Sir Edwin Chadwick’s American half brother), an early proponent of baseball as a participant sport, was baffled and alarmed. Mr. Chadwick assumed that these crowds were made up largely of bettors and feared that an association with gambling would hurt the game’s reputation. As he later came to realize, most of these spectators came out not to gamble, but to root for clubs that represented their neighborhood and their city. They were America’s first fans.

By the late 1860s, a game that 15 years earlier had been known to fewer than a hundred residents of Manhattan was played and watched by hundreds of thousands from coast to coast.

Dr. Jones was one of the first to see that interclub and intercity rivalries could improve and promote the sport. The key year was 1857. Interclub matches created a need for common playing rules and protocols, so 16 clubs—all of them in and around New York and Brooklyn—held a convention to address these issues. The following year they formed a permanent governing body with the aspirational name of the National Association of Base Ball Players, or NABBP. In November 1857, Dr. Jones led a bloodless coup to take over the Excelsiors. As president of the Excelsiors he represented the club at the 1858 NABBP convention, where he was elected president. Dr. Jones was now positioned to execute his plan to build the Excelsiors into a top-rank baseball club and use it as a vehicle to popularize the sport. The first step was to upgrade their playing talent. Dr. Jones recruited promising athletes through his personal and professional connections, including from P&S itself. The finest of these was first baseman Andrew T. Pearsall (P&S 1861), whose superb fielding—at a time before the invention of baseball gloves—was attributed to his surgeon hands. (Dr. Jones had been Dr. Pearsall’s preceptor at P&S.) Poaching players from other clubs was considered unethical, but in a clever evasion, the Excelsiors acquired team captain and catcher Joseph Leggett, a Brooklyn fireman, via a club merger. Mr. Leggett pioneered the use of weight training for baseball and put the Excelsiors on a rigorous training regimen. Records do not reveal whether Mr. Leggett had any connection to Jones’ gymnasium (which was two blocks from his firehouse), but policemen and firemen of the time were particularly active in boxing, gymnastics, and weight lifting. After Mr. Leggett persuaded young pitching prospect James Creighton to use weights, Mr. Creighton developed a nearly unhittable fastball and became the greatest pitcher of the 1860s. In another innovation, Dr. Jones formed farm systemlike arrangements with Brooklyn junior clubs that provided the Excelsiors with a ready supply of young talent. Other clubs followed suit; those that did not, such as the Knickerbockers, quickly became noncompetitive. The ostensibly amateur Excelsiors may have been the first club to pay their best players. They did so discreetly, by giving players or their family members sinecures or other favors. Thanks to the political connections of men like Dr. Wyckoff, for example, Mr. Creighton and his father held no-show patronage jobs in the New York Customs House.

Going into the 1860 season, Brooklyn was home to the top three or four clubs in baseball, and the Excelsiors were as good as any of them. As president of both the NABBP and the Excelsiors, Dr. Jones decided to introduce the New York game to the rest of America through a series of tours in which the games would be played by NABBP rules. These tours were baseball history’s first road trips. Though the New York game is the ancestor of modern baseball, different parts of America had their own bat and ball games before the Civil War. While the rules of these regional games differed considerably from those of the New York game, the basic playing skills—throwing, catching, batting—were similar. The 1860 Excelsiors challenged the best local players from Albany to Boston to Philadelphia to Baltimore and went undefeated, routing them by lopsided scores such as 24-6 and 50-19. James Creighton became baseball’s first national star. Forged in the crucible of the hypercompetitive New York-area baseball scene, the Excelsiors’ thrilling and athletic play convinced clubs across the country to convert to the New York brand of baseball. By the late 1860s, a game that 15 years earlier had been known to fewer than a hundred residents of Manhattan was played and watched by hundreds of thousands from coast to coast and was called the national pastime.

Dr. Jones and the 1860 Excelsiors stood atop the baseball world, but their time there was fleeting, partly because of the Civil War. The Excelsiors stopped playing matches in 1861, when more than 90 members of the team joined the military. This included Dr. Jones, who served as surgeon of the 52nd New York Militia and the 176th New York State Infantry, and many of his fellow P&S alumni. Pitcher Creighton did not serve, but he died in 1862 at age 21 from a strangulated intestine that became gangrenous. This must have been frustrating to watch for the physicians on the Excelsior club, who would have understood what was happening to Mr. Creighton but lacked both the surgical technology and the antibiotics that could have saved his life.

Another loss to the Excelsiors occurred in late 1862, when first baseman Andrew Pearsall (P&S 1861) disappeared from the club and his thriving Brooklyn practice. He resurfaced soon after in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Va., when he ran into an old friend there. According to a July 4, 1863, article in the New York Clipper newspaper:

The Excelsior Base Ball Club of Brooklyn recently expelled one of its members, A.T. Pearsall, for deserting the flag of the Union, and going over to the rebels. … During the past winter he left, and no one knew where he had gone. Some time since he was heard from in Richmond, Va., as a Brigade Surgeon, on the rebel General Morgan’s staff. He had charge of some Union prisoners … when he recognized a gentleman of Brooklyn, formerly a member of the Excelsior Club, and entered into conversation. He asked particularly about Leggett, Flanley, Creighton, and Brainard, whom … he wished particularly to be remembered to.

After the defeat of the Confederacy, Dr. Pearsall settled in the South. (Two decades after the war ended, the P&S alumni directory continued to omit any mention of his military career.) Dr. Pearsall practiced medicine until his death in 1905, and baseball historians remember him as a founder of the first baseball club in Richmond and a pioneer of baseball in Alabama.

In the postwar years, both Dr. Jones and his club became victims of their own success. Baseball was now truly a national sport and the Excelsiors could not compete with strong out-of-town clubs like the Philadelphia Athletics and the Cincinnati Red Stockings. The team gradually withdrew from sports and became a social club. Dr. Jones served as a city coroner and was appointed Brooklyn’s public health officer. In this capacity he directed that city’s response to the cholera epidemic of 1866, campaigning for improved sanitation laws, conducting aggressive health inspections, and cleaning up dirty city streets, tenements, and vacant lots. Even though none of these measures proved to prevent cholera, which is spread through water contaminated by bacteria, Dr. Jones’ sanitation and public health reforms improved lives just the same. Clearly practicing what he had always preached about staying in shape, Dr. Jones appeared in baseball old-timers games into his 50s. In 1898, when he was 75, he won a citywide bowling tournament.

Dr. Jones played no role in the professional baseball era, which began in 1871. In that year the National Association, the first national professional baseball league, took the place of the old amateur NABBP. In 1876 the National Association was succeeded by the Midwest-based National League. These professional sports organizations were innovative in many ways. They were the first to turn clubs into corporate franchises. They signed players to contracts and openly paid them salaries. They built elaborate ballparks and laid the foundation for today’s multibillion dollar team sports industries. They did not, however, invent a sport. The amateur athletes of the New York game—led by Dr. Jones and his fellow pioneering baseball-playing physicians from P&S—had already given them baseball.

- Log in to post comments