Patients as Teachers in Quest for Answers to Rare Diseases

Every year as part of the genetics block for first-year medical and dental students at Columbia, Wendy Chung, MD, PhD, the Kennedy Family Professor of Pediatrics in Medicine, includes a session she calls “Patient as Professor.” Since 2018, Luke Rosen has given the lecture, speaking on behalf of his family, including daughter Susannah, who was 2 years old in 2016 when Dr. Chung became her doctor.

Susannah has degenerative KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder (KAND), a rare genetic disorder. Her diagnosis transformed her father from an actor and teacher into the co-founder of KIF1A.ORG, a $1.5 million nonprofit patient advocacy group founded with his wife, Sally Jackson, to identify families with children like Susannah and create a community driven to urgently find a cure for their kids. “This mission to cure KAND and galvanize an ultra-rare disease community required critical guidance from Dr. Chung,” says Mr. Rosen.

In 2021, the day of Mr. Rosen’s annual lecture coincided with a school holiday, so he and Sally brought along Susannah (“Sus”) and her older brother, Nat. At the end of his talk, Mr. Rosen asked Sus if she wanted to add anything. The 7-year-old brunette rolled onto stage in her wheelchair, took the microphone from her father, and crooned one of her favorite Disney ballads—“Let It Go” from the movie “Frozen,” embellished with her own stylings. “Susannah is a pioneer,” says her father. “People who see how she communicates and how she sings, those people want to help her.”

Sally Jackson with her daughter, Susannah Rosen. Photograph by Christopher Ryan Jones.

Sally Jackson with her daughter, Susannah Rosen. Photograph by Christopher Ryan Jones.Back in 2016, relatively little was known about the molecular mechanisms by which KIF1A would progressively steal Susannah’s words, her sight and mobility, and, most recently, even the restorative rhythms of a REM cycle. With no cure on Susannah’s horizon, her parents clung to hope. They asked Dr. Chung what they could do to extend her quality of life. Find more people with KIF1A, Dr. Chung told them. At the time, just 15 cases of KIF1A had been described. Since then, the nonprofit Susannah’s parents founded has identified more than 350 people with KAND in more than 25 countries and, together with a growing community of families, raised funds to support the only global KIF1A Patient Registry and National History Study—housed in Dr. Chung’s lab.

Says Mr. Rosen, “She gave us a roadmap of what we had to do to forge progress.”

Dr. Chung started medical school in 1990, the same year that the Human Genome Project launched.

In the decades since, the field has grown by leaps and bounds, with Dr. Chung often leading the way. Now chief of the Division of Clinical Genetics in the Department of Pediatrics and medical co-director of the university’s genetic counseling graduate program, Dr. Chung has identified more than 50 genetic conditions and regularly partners with families—as with KIF1A.ORG—to combine natural histories and basic molecular research in pursuit of better testing, clinical care, and cures.

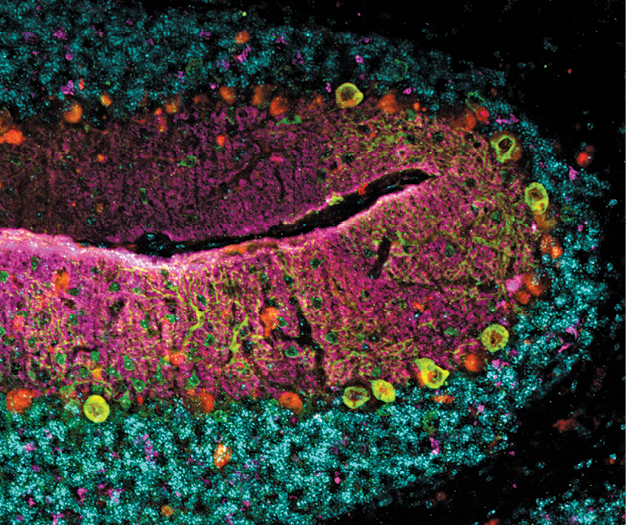

The cerebellum of the Kif1a leg dragger mouse model for KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder, a rare genetic disorder. Courtesy Wendy Chung..

The cerebellum of the Kif1a leg dragger mouse model for KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder, a rare genetic disorder. Courtesy Wendy Chung..That effort kicked into high gear in November 2021 when the National Organization for Rare Disorders—NORD—named Columbia University Irving Medical Center/NewYork-Presbyterian a Center of Excellence for rare diseases under Dr. Chung’s leadership.

A disease is considered rare if it affects fewer than 200,000 people. More than 7,000 rare diseases affect 25 million to 30 million children and adults in the United States, spanning every organ system and every stage of life. Combined, rare diseases rival diabetes rates at the population level, yet FDA-approved treatments are scarce. Even diagnoses can be elusive because of the lack of clarity about the underlying genetic causes. As at Columbia, each of the 31 institutions designated as a NORD Center of Excellence has experts across multiple specialties dedicated to meeting the needs of patients with rare diseases through clinical, patient education, and research programs.

“This is the Good Housekeeping seal of approval,” says Dr. Chung, whose patients credit her with a knack for plain speaking on subjects both scientifically complex and emotionally fraught. “That nod from the National Organization for Rare Disorders is really important in terms of patient care. It is an endorsement that we’re not just providing excellent clinical care today, but thinking about the future and pushing the envelope in terms of treatments.”

Take, for example, Dr. Chung’s work on spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the leading genetic cause of death among children under 2 years of age. A recessive gene for the degenerative disease affects one in 54 Americans. One person in every 11,000 has two copies, leading to a shortage of the spinal motor neuron protein, which is vital for muscle development and movement. Over time, the spinal motor neurons of people with SMA waste away, leading to problems with movement and eventually breathing and swallowing as well.

In 2004, Dr. Chung partnered with Columbia’s Darryl De Vivo, MD, the Sidney Carter Professor of Neurology and also a professor of pediatrics, and the Spinal Muscular Atrophy Foundation to establish a clinical research network to better characterize SMA and set the stage for clinical trials. From 2014 to 2017, with a promising treatment on the horizon, Dr. Chung led the pilot newborn screening study of SMA in New York state that helped lead to nationwide adoption of the test in newborns. “Children are alive today and thriving because they got early diagnoses and had opportunities to start treatments that were not yet FDA approved but have since become available,” says Dr. Chung. “SMA is one of the greatest success stories in terms of being able to diagnose every baby and get them one-and-done gene therapy.”

Yet millions of people have one of the thousands of rare diseases that do not yet have FDA-approved treatments. They stand to benefit most from the NORD designation, says Dr. Chung, whose hundreds of peer-reviewed publications have elucidated the genetic underpinnings of such comparatively common diagnoses as autism, cancer, heart disease, and pulmonary hypertension.

“It gives me great hope that one by one we’ll be able to address these rare diseases in ways that are safe, lasting, and help the greatest number of people possible.”

Beyond the trust engendered among patients seeking clinical care, the NORD designation will create the conditions for families, clinicians, and scientists to scale up their efforts. “The more rare the disease, the more challenging it can be to find enough people with the condition. It is also challenging to convince funding agencies and philanthropists that it’s important enough to put resources toward that effort,” says Dr. Chung. “With 90% of those diseases, we’re still in that slogging-it-out phase in terms of describing the natural history of the disease, identifying its mechanism, discovering therapeutic strategies.”

Often, the search to uncover a genetic mechanism for a disease and the search for strategies to alter its molecular pathways move forward together. Throughout her career, Dr. Chung has championed the rights of patients in that process, helping to shape the ethical and legal context for genomic discovery and therapeutics. In 2013, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down patents on natural genes, with Dr. Chung as the first plaintiff. She worked with the ACLU on behalf of people at risk of hereditary breast cancer who could not access testing due to patents on the relevant genes. In the wake of that victory, the availability and affordability of genetic diagnostics of all types have expanded significantly.

Luke Rosen with daughter, Susannah Rosen, son, Nat, and wife, Sally Jackson.

Luke Rosen with daughter, Susannah Rosen, son, Nat, and wife, Sally Jackson.Today, Dr. Chung is in the early stages of developing what she calls a modifiable “news you can use” diagnostic panel for newborns. Envisioned as a genomic corollary to the universal screenings that already detect phenylketonuria, cystic fibrosis, and now SMA, the panel would give every family access to diagnosis and treatment even before symptoms manifest and damage becomes irreversible. Families would receive diagnoses as clinical trials—or FDA-approved treatments—become available.

“I can feel the momentum rising in terms of clinical trials. Sickle cell disease is one example,” says Dr. Chung. “It gives me great hope that one by one we’ll be able to address these rare diseases in ways that are safe, lasting, and help the greatest number of people possible.”

Even as Dr. Chung tackles population-scale strategies for early screening and treatment to give every newborn the best shot at a healthy future, she continues her efforts on behalf of patients like Susannah Rosen, living with rare diseases for which cures have not been found.

“As a NORD hub, we can be a resource for all physicians,” says Dr. Chung. “I’m hoping that we can help researchers share what we’ve learned. That includes best practices in terms of how to share information, honor privacy, and set up research infrastructure for collecting and storing data. We have so much we need to learn that we can’t afford not to work together on behalf of patients.”

- Log in to post comments